Introduction

Overview of Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C is the most common chronic viral blood-borne infection in the United States. It is estimated that 3.9 million people (1.8% of the population of the U.S.) have been infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV), and 74% of these individuals, or 2.7 million, are chronically infected.1 The majority of affected individuals have no symptoms when they first acquire the disease and may not develop symptoms until 10-20 years later. Of those chronically infected, 50% - 60% will develop evidence of chronic liver disease (manifested by elevated liver function tests), 10% - 20% will develop cirrhosis, and 1% - 5% will die from hepatocellular carcinoma or complications from chronic liver disease.1,2 Risk factors for more rapid progression to cirrhosis include male gender, age greater than 40 years at time of infection, co-infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or hepatitis B virus (HBV), obesity, and alcohol use.3 HCV has become the most frequent indication in the U.S. for liver transplant, accounting for 37% of liver transplants in 2000.4 In 1997, the direct and indirect costs of HCV in the U.S. were estimated at $5.46 billion (comparable to the 5.8 billion spent on asthma in 1994).5

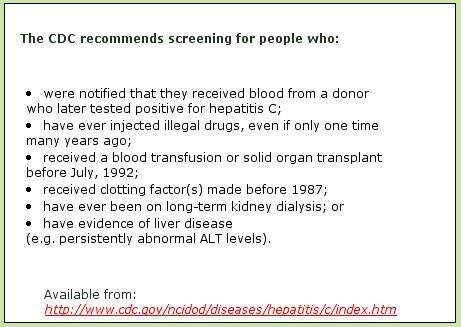

According to the CDC, risk factors for HCV include contact with blood or body fluids from a person infected with HCV. This exposure can occur from sharing injection drug use equipment, blood transfusions, or solid organ transplants before July 1992, receipt of clotting factor(s) made before 1987, and long-term kidney dialysis.2 In the period of 1995 – 2000, 68% of newly-acquired cases in the U.S. occurred among injection drug users, 18% were reported to be sexually acquired, and 4% occurred in occupational settings.6

The current standard of care for treating HCV involves interferon-based therapy, which is successful in eradicating the virus nearly 50% of the time.7 Successful drug-based treatment is defined as a lack of measurable virus 6 months after the conclusion of therapy (known as sustained virologic response) and varies by genotype. Of the six genotypes identified, treatment for type 1, the most common genotype in the U.S., is successful in eradicating the virus 30% - 40% of the time. Response rates with genotypes 2 and 3 are much higher, approaching 80%.7

Other methods of treatment of HCV involve complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) approaches, which alone or in combination with drug-based approaches can improve the quality of life for persons with HCV.

Hepatitis C Screening and Diagnosis

The basic screening test for HCV is offered in medical settings and by most local health departments. The initial screening test is an inexpensive test (approximately $15) called the enzyme immunoassay (EIA), which detects HCV antibody. In settings where the prevalence of infection is low, up to 20% to 50% of positive EIA test results may be falsely positive.8 The recombinant immunoblot assay (RIBA), another antibody detection test, is more specific than the EIA and can be used to rule out false-positive EIA tests. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test measures HCV RNA, signifying that a person has circulating virus. These confirmatory tests are much more expensive than the initial screening test and are usually performed by a primary care physician or gastrointestinal specialist.

When a person initially acquires HCV, circulating virus is present (and measurable by PCR) within 1-2 weeks, and circulating antibodies are usually present 7-8 weeks post-infection. There is also an increase in liver enzymes such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT). About one-third of people develop symptoms of hepatitis, such as jaundice. If RNA is present 6 months after infection, the individual is considered to have chronic HCV infection.

|

Serum ALT levels can be used for assessing disease activity. Persistently elevated ALT levels suggest the development of chronic liver disease and the need for further work-up, such as genotype identification or biopsy. The measurement of ALT levels during antiviral treatment is also an important means of monitoring response to treatment.

The genotype test identifies HCV genotypes and subtypes. There are 6 genotypes and >90 subtypes of HCV known. In the U.S., 70% of HCV infection is caused by genotypes 1a or 1b. Knowledge of the genotype can be used to predict the response to treatment. For example, patients with genotype 2 and 3 are more likely to have a sustained virologic response to interferon alpha than those with genotype 1a or 1b.7

A liver biopsy is performed on individuals with chronic HCV infection to detect the level of physical damage to the liver. A biopsy is performed in a medical setting on an outpatient basis and determines both the severity of liver disease and the degree of fibrosis, or scar tissue, in the liver. A liver biopsy also serves to rule out other forms of liver disease such as steatosis (fatty liver), cirrhosis related to chronic alcoholism, liver injury or damage due to iron overload.

Hepatitis C in Oregon

Based on national prevalence data, it is estimated that 64,000 Oregonians are currently infected with HCV. Tracking the number of acute (newly-acquired) cases of HCV that occur each year in Oregon is problematic, however. Although acute cases of HCV are reportable to the state, only 15 – 20 cases are reported each year, which is most likely a vast underestimate. Most patients with HCV have no symptoms at the time of initial infection. Other reasons for under-reporting are that patients may not seek health care even if they do have symptoms, practitioners are often unaware of acute case reporting requirements, and local health departments have no easy way to distinguish between acute and chronic infections based solely on laboratory reports. However, despite the lack of data on the number of new infections that occur annually, several studies in Multnomah County and in the state of Oregon have provided insight into the HCV epidemic in Oregon.

In 2000, the Multnomah County Health Department offered HCV testing and evaluated risk factors for HCV among clients seeking HIV testing. They found that 55% of persons who admitted to injection drug use were positive for HCV, while the prevalence of HCV was much lower in persons who only had household or sexual contacts with an infected person. Similarly, a 1998 study of inmates entering the Oregon State Penitentiary found that 30% of inmates had antibody to HCV, and 62% of persons who had used injection drugs had antibody to the virus.

In 2000 – 2001, a CDC-funded study in Multnomah County found that 70% of patients with chronic liver disease seen by gastroenterologists were HCV-positive, of whom 70% had a history of injection drug use at some time in their past. Thirteen percent of these HCV patients had most likely acquired HCV from a transfusion, and 5% reported high-risk sexual activity as their only risk factor.

In summary, studies in Oregon have confirmed what researchers in the rest of the U.S. have also seen, that the prevalence of HCV is particularly high among injection drug users and much lower in patients reporting high-risk sexual behaviors. The corrections population also is at high risk, similar to what has been observed elsewhere.

Hepatitis Prevention in Oregon

Within DHS, three programs (ACDP, Immunizations, and HIV/STD/TB) each have some responsibility for hepatitis prevention or interaction with populations at risk for hepatitis. ACDP is primarily responsible for surveillance for acute cases of hepatitis A, B, and C, and researchers in ACDP have been involved in several CDC-funded studies looking at the epidemiology of chronic liver disease and the prevalence of HCV in high-risk populations. The Immunization Program emphasizes outreach and distributes vaccine statewide to eligible providers, county health departments, and delegate agencies. They manage the perinatal hepatitis B program and provide hepatitis A and B vaccine to children eligible for Vaccine for Children (VFC) funds, and distribute vaccine to additional children and certain categories of high-risk adults through 317 funds from CDC. In 2003, they distributed unspent carryover 317 funds to 29 pilot projects in local health departments (LHDs) and correctional facilities around the state that provided hepatitis A and B vaccine to high-risk adults. The responsibilities of the HIV/STD/TB Program include management of HIV education and service delivery, patient care and outreach, incarcerated patient programs, and harm reduction programs throughout the state. As such, they have contact with many of the populations also at risk for HCV infection.

Prior to 2003, there was no statewide guidance or consistent approach to the prevention and management of hepatitis C virus in Oregon. With funding through the CDC's Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity (ELC) cooperative agreement, Dr. Ann Shindo was hired as the state HCV coordinator in August 2003. Housed in HIV Prevention, she has primarily been involved in developing and conducting a state HCV needs assessment among health department, mental health and addiction professionals. While conducting this assessment, Dr. Shindo has begun assisting counties in identifying and building on existing HIV and STD resources and facilitating integration of HCV services into appropriate public health programs. Doing this has provided counties with guidance for infrastructure development that fulfills county-specific needs. By no means complete, these first steps to HCV program development at the local level have been helpful in determining the strengths and gaps within the current HCV resource base across the state.

Results from the needs assessment of LHDs show that 29 (89%) of 35 LHDs are conducting some HCV screening. Many will only provide screening to clients who can afford the $15 - $20 fee, and only two have comprehensive testing and counseling procedures recommended in the CDC Viral Hepatitis Screening protocols.9 Seventy-seven percent of LHDs refer HCV-positive clients to at least one of the following: primary care physicians, the Oregon Health Plan, mental health or addictions services, and social support groups. Only 29% of those LHDs who report some type of referral indicated that they thought the client would receive good or appropriate care, and only two suggested that care would be excellent, or impressive. Few of these LHDs collaborate with local agencies that could support HCV-positive people, and most cited resources (e.g. money and staff costs), and the lack of an appropriate referral infrastructure as the main barriers preventing them from conducting HCV testing and counseling in their county.

Thus, it is clear that some HCV screening and referring to appropriate resources is occurring in Oregon. Unfortunately, this is not universal and the ability of many LHDs to offer screening and referrals to providers or other support services in their community is limited due to the lack of resources.

The hiring of a state HCV coordinator and the 2003 legislation mandating the development of a statewide plan have led to increased collaboration between ACDP, Immunization, and HIV/STD/TB at the state level. The participation of all three programs in the statewide planning process has created a foundation for better integration of the three programs that will ideally lead to the integration of HCV counseling and testing into HIV settings and increase the likelihood that people living with HCV are targeted for hepatitis A and B vaccine. The three programs have created an in-house hepatitis taskforce that will meet monthly in order to implement the recommendations of the SVHPG. Additionally, a 10-member HCV advisory group, consisting of members of the original SHVPG and representatives from more diverse communities in Oregon will be formed. The role of this group will be to oversee implementation of action steps within the strategic plan, increase partnerships necessary for implementation, promote inclusion of diverse groups of people into the implementation process, conduct evaluation and continuous quality improvement strategies in relation to plan implementation, and advocacy. This group will meet bimonthly for the first year after the plan is submitted to the legislature and less frequently thereafter.

Appendix A - Management of Hepatitis C

Guiding Principles of Interferon-based Antiviral Therapy

- Management of chronic HCV, with the specific goal of viral eradication, should be evidence-based and reflect understanding of the natural history of the infection as well as the limitations of current therapy. Decision-making should follow these principles:

-

- Though very appropriate for some, viral eradication treatment is not for everyone.

- Treatment is costly and often associated with significant adverse effects.

- In many cases, viral eradication is not necessary, safe, or appropriate.

- Selection of patients for treatment with the intent to eradicate HCV should be highly individualized.

- A careful benefit to risk analysis should always be done, incorporating both patient and disease factors.

- Final decision to treat should be predicated, minimally, on

- the severity of liver disease,

- the likelihood of response,

- the potential for serious adverse effects of therapy

- and patient's level of motivation for therapy.

- Although current drug-based therapy is effective in clearing HCV in about one half of those treated, only 15-20% of chronically infected, untreated individuals will develop cirrhosis. Thus, therapy may be safely deferred for the following patients:

-

- Individuals with absent or minimal fibrosis on biopsy, especially if genotype 1.

- Patients whose progression of liver disease is slow, often taking years to progress, especially if in an early stage at the time of initial evaluation.

- Interval liver biopsy approximately 5 years after the first is prudent in the follow-up of those not treated.

- The following patient conditions are associated with either:

-

- high risk for serious iatrogenic problems

- low response rates

- potential lack of adherence to therapy.

- Treatment of these patients should only be pursued on a case-by-case basis by providers with high patient volume and expertise in treating these conditions:

-

- Active use of alcohol (continued alcohol use during therapy adversely affects response to treatment)

- Active injection drug use (although injection drug use does not adversely affect response to treatment and concurrent methadone use is not a contraindication to therapy, there is only limited data available on the feasibility of treating IDUs)

- Decompensated cirrhosis (response to treatment is lower than in patients without cirrhosis).

- Certain pre-existing inadequately controlled medical or psychiatric conditions that carry a higher risk of harm if treated.

Specific suggestions related to viral eradication therapy should be evidence-based and approximate published guidelines (e.g. AASLD Practice Guideline: Diagnosis, Management, and Treatment of Hepatitis C. Strader DB et al. Hepatology 2004;39(4):1147-1171., NIH Consensus Conference Development Statement: Management of Hepatitis C - 2002, June10-12, 2002. etc.)

- Management of Chronic Hepatitis C, with the goal of long-term maintenance or support, should follow these principles:

-

- The long-term value of agents commonly prescribed for viral eradication remains unproven.

- Emphasis should be placed on the avoidance of alcohol, selection of the least hepatotoxic alternatives among medications prescribed for other conditions, pursuit of ideal body weight, nutrition, and vaccination for hepatitis A and B (if not already immune).

- A number of agents and modalities within the scope of CAM may be of value.

- Agents known to be associated with hepatotoxicity should be investigated and their use discouraged. Milk Thistle (silymarin) in pure preparation has proven safety.

- Use of over-the-counter agents directed at liver support should be discouraged unless used under the supervision of a licensed allopathic or naturopathic clinician knowledgeable about HCV.

- CAM modalities of all types should be taken only under guidance of a licensed CAM provider with expertise in liver disease.

Guiding Principles of Complementary and

Alternative Medicine (CAM)

- Goals

-

- 1. Use adjunct natural therapies in conjunction with interferon-based treatment:

- to enhance effectiveness of conventional therapy

- to reduce side effects of conventional therapy in order to increase likelihood of completing full duration of interferon-based treatment

- 1. Use adjunct natural therapies in conjunction with interferon-based treatment:

-

- 2. Use alternative therapies when interferon-based treatment is refused, withheld, unavailable, or unsuccessful for:

- detoxifying

- liver protection - anti-fibrotic, anti-oxidant

- anti-viral and immune support

- 2. Use alternative therapies when interferon-based treatment is refused, withheld, unavailable, or unsuccessful for:

-

- 3. Enhance patient quality of life through:

- education about - nutritional optimization, lifestyle improvements, and stress reduction

- decongestion of the liver and reduction of systemic toxicity

- enhanced nutrient absorption and assimilation

- decreased systemic inflammation

- enhanced functioning of elimination pathways of the body

- 3. Enhance patient quality of life through:

Recommendations for CAM Management of HCV

- Identify and evaluate CAM treatment protocols for the management of HCV in the above areas.

- Train CAM providers through an approved CE class in the management of HCV to ensure a high level of familiarity and competence in CAM treatment of HCV.

- List on web site those providers that have completed the CAM CE class so that patients and referring physicians seeking a CAM provider can choose someone with competence in this area.

- Education of both allopathic doctors and naturopathic doctors to allow effective integration and co-ordination of therapies to provide optimal care for HCV patients.

- Education of lay public in the use of over-the-counter natural medicines.

Hepatitis Links

Model Programs for Hepatitis A, B, and C Prevention

Center for Research to Advance Community Health: Information, education and support for people with hepatitis C and their caregivers.

References

1. Alter MJ, Kruszon-Moran D, Nainan OV, McQuillan GM, Gao F, Moyer LA, et al. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus in the United States, 1988 through 1994.

2. CDC. Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and HCV-related chronic disease. MMWR 1998, 47(RR-19): 1-39.

3. Seef LB. Natural history of chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2002;36:S35-46.

4. Kim WR. The burden of hepatitis C in the United States. Hepatology 2002;36:S30-34.

5. Leigh JP, Bowlus CL, Leistikow BN, Schenker M. Costs of hepatitis C. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:2231-2237.

6. Alter MJ. Prevention of spread of hepatitis C. Hepatology 2002;36:S93-S98.

7. DiBisceglie AM, Hoofnagle JH. Optimal therapy of hepatitis C. Hepatology 2002;36:S121-S127.

8. Hyams KC, Riddle J, Rubertone M, Trump D, Alter MJ, Cruess DF, et al. Prevalence and incidence of hepatitis C virus infection in the US Military: A seroepidemiologic survey of 21,000 troops. Amer Jrnl of Epi 2001;153:7694-7770.

9. CDC. Viral hepatitis counseling 2003. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Viral Hepatitis Branch.

The Roseburg Risk Reduction Needle Exchange program is offered through the HIV Resource Center, a project of Douglas County AIDS Council (DCAC).

DCAC is a private non-profit organization 501 (c)3.

Through the HIV Resource Center, DCAC maintains emergency funds, housing assistance, transportation assistance, case management, and referrals for people living with HIV. We promote risk reduction in our community through outreach programs, HIV testing, counseling, speakers bureau, information line and distribution of educational materials to all ages.

If you would like to be part of helping to make your community a better place, just give us a call to discuss donating your time, efforts, materials, or funds. We are all in this together, and together WE CAN MAKE A DIFFERENCE!